Searching through the National Museum of the American Indian records, I stared at a single receipt from Paris dated 1927 that simply said “vase.” I set the small slip of paper aside and thought, “I’ll never figure out which vessel that is.”

Yet 13 years later, I finally discovered the answer to this and many more mysteries hidden within the museum’s collection. That receipt was among the hundreds of thousands of documents, journal entries, photos and handwritten notes that have been matched with their corresponding items through an intense, multiyear effort.

This restoration of information has been crucial to helping Indigenous peoples reunite with cultural items removed from their communities, often generations ago. “Understanding the origins of the items in the collection—where they come from, who they belonged to, how they were used, how they were collected—provides critical context and tells an important story about the life of the belonging,” NMAI’s Head of Conservation Kelly McHugh explained. “Communities need to know how their belongings ended up in NMAI’s collection as they are considered relatives and, in many cases, relatives that have gone missing.”

By piecing together clues from the archives, we have uncovered hidden stories that reconnect Indigenous communities, artists and others with these items. We have also discovered a vast network of dealers, collectors, anthropologists and archaeologists who during the past century helped build the only national collection dedicated to the art, history and living cultures of Indigenous peoples across the Western Hemisphere.

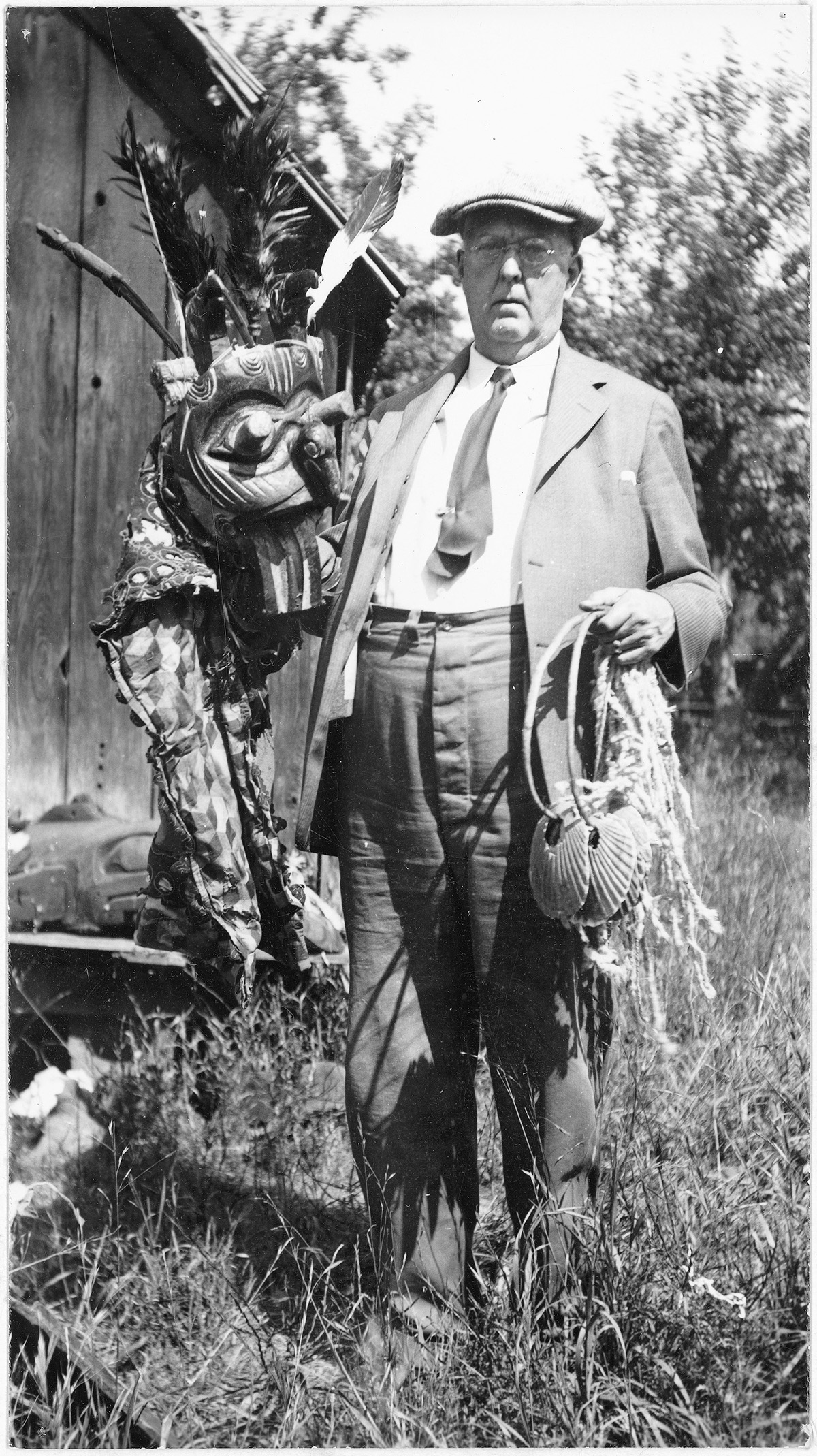

George Heye, holding a Snuneymuxw (Nanaimo) mask and rattle in British Columbia, Canada, in 1938. He used his vast collection from the Americas to found the Museum of the American Indian–Heye Foundation.

Photo by W. A. Newcombe; NMAI Archives P13426

Growing an Institution

What is today the National Museum of the American Indian began with the vision of one man. George Heye was a trained electrical engineer turned investment banker and the son of a wealthy German immigrant who made his fortune in the oil industry. Heye was fascinated with Indigenous cultures from an early age and began collecting arrowheads while at Lake Hopatcong in New Jersey. He purchased the first item for his collection, a Diné (Navajo) deerskin shirt, in 1897 at the age of 23.

Within a few years, he began amassing a large amount of Indigenous cultural materials and referred to this collection as the “Heye Museum.” In 1904, he wrote to his colleague archaeologist George Pepper that, “The young museum has taken on quite a business-like air. I am busy cataloging now during all my spare time and have just reached no. 1,250 and still have several hundred specimens yet to number.”

By the following year, he began talking about founding an institution solely dedicated to the study of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Using his personal wealth, he spent the next decade building a research staff, sponsoring expeditions and funding publications about the work of the “Heye Museum.” By 1908, Heye needed to develop a plan to care for his growing collection. He struck a deal with George Gordon, director of the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia, and in 1909, a portion of Heye’s collection was loaned to the museum, where it could be exhibited. Heye also served on the museum’s Board of Managers. By 1916, Heye had finally gained enough support of several wealthy benefactors to found his own institution, the Museum of the American Indian–Heye Foundation (MAI).

Cultural items came to the MAI in various ways. Heye’s museum staff of professional anthropologists and archaeologists brought items back from their expeditions and excavations. He also developed a vast network of contacts who would help locate objects for purchase from Indigenous individuals, dealers, collectors or auctions. The institution would also exchange items with other museums or be given gifts and bequests. Missionaries, farmers, Indian agents, diplomats, engineers, artists and others sold or donated items to the growing institution. Upon Heye’s death in 1957, MAI’s collection included more than 700,000 items in addition to numerous photographs, rare books and other archival materials.

Heye has often been portrayed as an obsessive, erratic collector, concerned only with acquiring more material. However, research indicates that Heye had focused collecting priorities and strategies. In addition, the emphasis on Heye as a sole collector has obscured the thousands of individuals involved in the creation of the MAI collection. Those contributors who have been in the shadows are now coming to light and providing us with new understandings of the museum’s practices as well as the broader history of Indigenous art collecting in the 20th century.

The Museum of the American Indian–Heye Foundation as photographed in 1941.

Photo by N. L. Stebbins; NMAI Archives P02974

Lost Connections

When Heye began cataloging his personal collection in 1904, he did so on 3-by-5-inch cards. The records usually only included a catalog number, the object’s name, culture or geographic region, and minimal source information. Collectors or Indigenous individuals deemed notable might be included, but thousands of items were simply described as purchases with no information about from whom the object had been acquired. For many years, collection documentation was kept in files organized by the collector’s name or, when available, an item’s source. However, as many files did not have a direct reference linking them to objects, retrieving information about specific items was difficult.

Heye’s successors as directors of MAI—Edwin K. Burnett from 1956 to 1960 and Frederick J. Dockstader from 1960 to 1975—inherited an understanding of the collection and its filing system. Burnett also created systems to document museum activities, including the compilation of gift, exchange and loan rosters. Dockstader saw the value in the archives and worked to expand them with the acquisition of papers from former MAI staff, such as archaeologists Pepper and Mark R. Harrington. These included field notes of MAI expeditions along with correspondence and photographs.

In 1974, the museum hit a particularly rocky period. Dockstader’s sale of the museum’s collection items without MAI Board approval led to a New York State Attorney General investigation, and MAI dismissed him in 1975. Dockstader’s departure led to a tremendous loss of institutional knowledge. The MAI was faced with completing a court-ordered full inventory of the collection, and focus was placed on that work for the next several years as well as finding a new home for the financially burdened MAI.

By the time the MAI collection was transferred to the Smithsonian Institution in 1990, the collection had grown in number to nearly a million objects and photographs. MAI’s absorption into the Smithsonian further disrupted connections between the collection and its documentation. In 1999, the paper records of the MAI were transferred to the NMAI’s Cultural Resources Center newly built in Suitland, Maryland. However, as staff members had been busy working on opening the new George Gustav Heye Center in New York in 1994, moving the object collection from New York to Maryland from 1999 to 2004 and then opening the National Museum of the American Indian on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., in 2004, they could not complete the processing of the collection until 2011.

Another complication was that a portion of the MAI archives kept at the Huntington Free Library in the Bronx was not transferred to the Smithsonian with the rest of the collection. In 1930, the MAI lacked space for their growing rare book and archival collection, and MAI patron Archer Huntington built an addition to the Huntington Free Library to serve as the repository for MAI’s material. The library was given 40,000 volumes on Indigenous archaeology, ethnology, history, rare books and significant manuscripts as well as documentation directly related to MAI collections and expeditions.

While MAI staff considered this material to be part of the MAI collection, the library’s trustees disagreed. After 15 years in court, the Smithsonian lost its claim to the material in 2004, and the Huntington Free Library sold the collection to Cornell University in New York, where it remains today. This loss to the NMAI further disconnected MAI archival documentation from the collection.

Recovering Histories

The Retro Accession Lot Project was launched in 2010 to locate, standardize and digitize collections documentation so that they would be fully searchable and accessible to staff, researchers and Indigenous communities. An “accession lot” is a numbering system that records an item or group of objects that were acquired from a particular source on a particular date. With this accession information, NMAI could begin to rebuild the provenance, or record of an object’s ownership, for the entire collection.

Rather than starting with an object and trying to locate information about it, it was decided to start with the archival documentation and match it to the objects. This strategy changed everything. With digitized documents, we could finally piece together information found in different locations in the archives. Some documentation on its own might not tell the full story, but when paired with other pieces, the picture got clearer and gave a better springboard for research, something we never had before.

In 2012, I joined the project as the primary researcher. Over time I became more familiar with the collecting strategies of the MAI and its founder George Heye. I began keeping a timeline to track the whereabouts of museum staff through the years to better understand their motivations and collecting habits. I identified collectors and sellers, determining whether they kept notes or photographs, and tried to narrow down the usual suspects that were sources of objects in different regions. In 2015, the project expanded to include reviewing archives at other institutions, including Cornell University. This also sometimes meant conducting genealogical research on individuals to track the path of items from hand to hand.

Tackling the provenance history of a museum collection of this size has been an incredible undertaking, but the result has been worth it. We have made the collection more accessible and obtained a better understanding of when and how objects entered the museum. We have also discovered the names of thousands of individuals who were never before associated with these items. Restoring this rich history allows the NMAI to offer Indigenous communities, researchers and museum visitors the most accurate information about this vast collection. It also helps the museum reckon with its history of separating Indigenous peoples from their cultural heritage.

“This project has an enormous impact on engagement with collections items,” said NMAI’s Head of Collections Care and Stewardship Cali Martin (Osage/Kaw). “The dots are finally connected, which means we can provide an incredible amount of information to our constituents.”

“Conservators attempt to use the material evidence to help understand the story of an object. The Retro Accession Lot Project helps us connect the material evidence to the history, putting everything in context. This results in more informed and responsible conservation, care and stewardship,” said McHugh. “The provenance information revealed because of this project also plays a critical role in helping Indigenous communities understand the past to pursue ethical return or shared stewardship arrangements for the future.”

Although we have revealed fascinating connections through this project, the work is far from over. We are excited to see what we will discover next.